Building a common agenda around an agroecological urbanism is necessary and promising.

Where can we start the conversation between agroecological farmers and cities?

Taking care of soil carers

“Soil care is a practice. It is something that happens day in and day out. In that sense, soil policy should not only be about how to protect soils, but is also about how to take care of the people who take care of soils.”

Hans Vandermaelen

Soil care is a new and inspiring narrative for public policy and spatial planning.

Within climate policies and sustainable development initiatives agroecology is today promoted under the popular discourse of nature based solutions and ecosystem services. This label seems to suggest that nature can be simply taped into as a source of service delivery. Agroecology, however, is a practice of growers and carers for the soil, and it is hard work. Agroecology relies on cultural soils that exist as they are regenerated and are dependent on the care work that is extended to them. Agroecology also requires the permanent presence of people that with all their senses pay attention to the seasons, the growth and maturing of plants, the weather conditions they suffer and benefit from, the interaction with a whole web of life that contributes to the health of plants and animals.

In urbanising societies farmers are pushed out of the landscape. Farming is often looked down upon and poorly paid. Urban functions are competing over farmland. Living close to farmland is made difficult. The interests of farmers are hardly represented in urban constituencies. Caring for the soil however is not possible when there will be no soil carers left.

See Zeven verhalen voor een radicale bodemzorg (Dutch)

The value of care

“When you are stretched, it is exactly the care that becomes really hard to do. And because it is so bad to not do something with care, we will still do so, but that is when the burnout happens. So it is because care is just this unrecognized, it is a classic old thing not to value care work and it is something that is very present in our agroecologies.”

Hari Biles, Compost Mentis

An endemic lack of resources limits the development of political pedagogies with care. Care is central to building more-than-human solidarities across city territories that recognise nature as urban, and are a foundational aspect in the formation of networks to mobilise agroecological food systems. In the context of the neoliberal city, where urban agroecological work often struggles to meet project core costs, and for farmers to pay high rent and cost of living, practitioners are often confronted with painful myriads of self-exploitation, self-care or giving up the ethical ambition to work with care. To be true to values. To build prefigurations of a just and sustainable society. For resourcing the connections already there in the movement. For resourcing the ability to take time to see, recognise, listen and care. Practitioners find themselves between axis of burnout working beyond available resources, and practice with limited embodiment at risk of a thin veil of agroecological values at splintered scales. A lack of resources squeezes the space for practitioners to reflect, strategise and collectivise learning. As the structures of the neoliberal city attempt to chase out cultures of care and solidarity, it is imperative to make space to develop sustainable strategies of care. Social security mechanisms, such as universal basic income or financial supports for farm-start are policy options that could be implemented and part of an agroecological urbanism.

Building on the effective use of zoning as a counterspeculative measure

Spanish cities have been able to protect farmland on the peri-urban fringe through effective land use instruments and the establishment of so-called agricultural parks. The measures have been reasonably successful in stopping the destruction of agricultural soils (Miralles I Garcia 2015, 2020) but show mixed results when it comes to delivering a transition towards agroecological ways of farming. Many of these agricultural parks are situated within naturally sensitive areas. This provides clear opportunities to link nature development and biodiversity goals to the establishment of conditions in which only certain farming models can thrive. Agroecology can be a gamechanger in such a context, as it is a farming model that can accelerate the evolution towards nature inclusive forms of farming and move beyond the conflict between environmental goals and agricultural development. Zoning measures aimed at protecting farmland may be supplemented with legal measures to protect high valued soils, as is the case in the Parque Agrario de Fuenlabrada, near Madrid (Yacamán Ochoa, Mata Olmo, 2017). The categorization of soils goes hand in hand with the installation of farming models that start from principles of soil care and the ecological reproduction of soil fertility.

Working and living on protected farmland

To be economically viable farmers need to be able to live close to the land and without additional housing costs. This concern is at the heart of the project Integral Agricultural Colony of Urban Supply (CAIAU) initiated in 2014 by the Unión de Trabajadores de la Tierra (UTT) after mobilisation by small producers. Each family has its house, works approximately 1 hectare of land and sells the produce in local markets (agroecological and non) and also organises box schemes for the inhabitants. The initiative of UTT also led the National Institute of Agricultural Technologies to work more seriously in family farming and agroecology. This argentinian initiative acknowledges the need to perceive agricultural land as part and parcel of a peopled landscape, in which the right to live on the land is part and parcel of a relationship of stewardship and not of land consumption.

See Las Colonias Agroecológicas (UTT) (Spanish)

Growing and living together within new patterns of use

The Lucavsala Island is located in the Daugava River in Riga. This island of about 150 ha is for a large part covered with an allotment garden complex of over 600 plots. As of today many of these allotment gardens are no longer cultivated. Some plots are reclaimed by a new generation of urban gardeners, many are being used as weekend and vacation spaces, and others are illegally occupied as spaces of residence. The allotment complex is under pressure of development. The tip of the island has been remodelled as an urban park, and the land adjacent to the park rezoned for high rise residential and mixed use development. This has led to mobilisation among some of the remaining growers to imagine an alternative future. These large allotment complexes, still present in close proximity to the urban centre, are part of the food growing infrastructure of the city and are an asset that other cities have long lost.

The participative design research of Sampling as part of the Urbanising in Place project explored development strategies in which the allotment complex would be maintained and its productive function intensified. Participants to the exercise discussed the possibility of hosting professional growers side by side allotmenteers. The exercise also looked into the possibility of clustering houses for farmers rather than building on individual lots, which has generally led to the trading of the productive for residential use. Building on the rich legacy of allotmenteering of socialist urban development, these exercises seek to articulate the conflict between the right to access growing spaces and the right to housing in collective patterns of use and move beyond the particular and fragmented interest of the entitlement to a singular plot (for growing and living).

Growing on damaged land

New farmers seeking access to land in the peri-urban fringe often end up with soils that have been poorly cared for. Soils may have suffered from soil erosion, have been compacted and partly sealed, may have been contaminated, etc. The Agroecology Lab of the Université Libre de Bruxelles built together with farmers a guide to make a simple assessment of the soil, starting from easy and accessible techniques that can be executed by growers themselves. The guide is distinctively built to work with living soils: rather than overly focussing on chemical composition, the guide is geared towards observing and enhancing biological activity, the soil’s structure and its water retention capacity.

Care for damaged soils is an integral part of an agroecological urbanism. While valuable soils should first of all be protected against the pressures of urbanisation, the conversion of land that was temporarily not cultivated has an important role to play as well. The rebuilding of top soils on such damaged lands should not be an individual responsibility of growers and could be facilitated. Farmers should be given time in which they can work on these lands without economic pressure and with the secure prospect of long leases in order to encourage long term care for the soil.

Sharing among family members, friends, neighbours and colleagues

In amateur gardening and livestock farming, an occasional or seasonal overabundance of produce is inevitable. In the Latvian context, not unlike other post-socialist states, the free sharing of surplus is still a common practice and rooted in a long history of auto-production. Sharing is not limited to family members, but includes a wider network of colleagues, friends, and neighbours. This tradition partly stems out of a sense of solidarity and dates back to times of Soviet occupation when food and other resources were scarce, and family members of different generations had to actively support each other. While today, sharing is no longer a bare necessity, interviews carried out as part of the Urbanising in Place project show that people find joy in offering others self-grown food, and feel pride for their own accomplishment. And even those in need do not hesitate sharing the surplus of their self-grown produce.

These practices are often not considered within sustainable food planning initiatives. Individuals and communities involved in informal practices of food sharing are not campaigning around such practices. Local farmers engaged in direct selling initiatives tend to replace informal traditions of sharing. Can we imagine urban food policies in which self-growing and sharing practices would be celebrated and valorized?

Spaces for collaboration

Atelier Groot Eiland is a social economy organisation committed to giving people a better chance on the labour market and has been active in Molenbeek, Brussels for over 40 years. The non-profit offers work experience, pre-training, employment support and job support. The organisation has grown to become a collection of mini-companies, offering training in a wide range of skills: the Bel Mundo and RestoBEL restaurants, the Bel'O sandwich shop, the Klimop carpentry shop, the Bel Akker urban vegetable gardens and pick-your-own farms, The Food Hub organic shop, the creative workshop and the bakery of ArtiZan, each have their own employees and customers, and thus respond to the needs of different neighbourhoods in Brussels. The organisation is particularly investing in connecting to the surrounding neighbourhood and actively strengthening a local Molenbeek identity – leading to a lovely mix of French and Dutch in their social media. More recently, Atelier Groot-Eiland has started a 1.5 hectare self-picking CSA project in the peri-urban area and is more and more approached by urban actors and local authorities to actively participate in urban redevelopments, acting as a socially driven and sustainable placemaker.

Beyond charity models and food waste

“Surplus” food discarded by the mainstream food supply chain is abundant, and there are often financial incentives to access it (i.e. it is cheap, or free). However, this is often food that is conventionally grown (using agrochemicals and pesticides), shipped from the other side of the planet, and unfairly paid to farmers and farmworkers, who struggle to obtain dignified livelihoods. Charity-based food projects often rely on donations to distribute the food to people in need, without challenging the injustices in the food systems that affect farmers and consumers.

One of the key challenges for community kitchens is to move away from this food (and these allocation models), and accessing agroecological food, which is healthy for people and for the planet, and grown and marketed with justice. This is particularly difficult when the aim is to source food locally (which is more expensive than imported food), when people most in need are on low incomes, and when culturally appropriate food can not be grown locally. The Granville Community Kitchen in London is an inspiring organisation in the North-West London. While at present, Granville is not yet able to organise food aid without surplus food from the mainstream food supply chain, they have undertaken several actions to provide as much as possible local, healthy and socially just food. One of the core values of the organisation is also to provide for culturally diverse dietary needs. For example, through a veg box scheme called ‘Good Food Box’ in a pay-what-you-can principle, they cater for a wide range of eaters, providing optional African and Carribean Heritage bags. By linking community supported agriculture (CSAs) models (producers-consumers alliances), with equity models (sliding scales of veg-box, to allowing the creation of an equity fund), and when necessary, by importing from agroecological producers cooperatives overseas, community kitchens can enable a much broader access to good food, that would otherwise only be available to middle classes.

No agroecology without decolonisation

“It is that big ecology of care, I would also say it’s a queering ecology. And by queer I mean about disrupting and dismantling white European straight male frameworks and contexts. And so we are decolonial in practice, and we go beyond just being feminists, as I said we’re queer and spiritual because a lot of us are coming with spiritual practices and beliefs. And so for us that solidarity is collective in arriving at collective understanding and values and each others offering something.”

Deirdre Woods, Granville Community Kitchen

The foundations of the modern agri-food system are in European colonial projects that have violently tried to destroy indigenous land, land practices and foodways. And so disrupting and dismantling white-supremacist, patriarchal and euro-centric knowledge structures is integral to forming agroecological economies and localised distribution networks. In terms of developing urban agroecologies, this includes the binaries of human vs. nature, urban vs. rural that underlie urban hegemonies and limit the ways of imagining and developing cities as agroecological places. Practices that support the collapsing of historical binaries, through processes of political contextualisation of urban life, re-humanisation, and positive identity formation, are critical to developing urban agroecologies.

Urban infrastructure can kickstart farming careers!

BoerenBruxselPaysans is a pilot project in the peri-urban fringe of Brussels seeking to offer new farmers the needed impulse to provide Brussels with local, healthy, qualitative and affordable food. Through the coalition of existing grassroots movements with government aid under the coordination of the Brussels regional authority and European funding, the project was able to set up a broad range of supportive infrastructure for starting farmers. The municipality of Anderlecht offers land as an espace-test or farmstart for farmers that want to test out their business model. The grassroots movement Début des Haricots offers practical training courses and links the test-farmers with their spin-off network GASAP—different consumer groups in the city of Brussels that are running a vegetable box-scheme. Maison Verte et Bleue runs a community kitchen and will help the local farmers to operate the future conserverie and packaging facility and Terre-en-vue, an access to land organisation, scouts more permanent and lasting land use agreements across the city for when farmers went through the testing period. The municipality of Anderlecht chose not to sell off residual agricultural infrastructure that marked the neighbourhood, but rather invest in the renovation and programming of these farm buildings to support growers and food initiatives in this part of the city. By focusing on infrastructure, BoerenBruxselPaysans creates literally the supporting environment that enables a constant inflow of new and transitioning farmers. It also creates a node in a wider landscape, holding the potential to offer their supporting infrastructure to many more farms in the area. Could we imagine the migration of the farm start to other locations, rather than moving the farmers that have invested in the soil and have in the meantime become networked within a local community?

Creating a shared future through soil care

The 'Roving Microscope’ is a community-based initiative that is looking into soil and exploring more-than-human ecologies based in and around Bethnal Green Nature Reserve in Hackney. With many people in urban areas alienated from the land, growing food, and soil, general knowledge about and connection with local soils are often limited. The Roving Microscope tries to directly answer this situation by bringing people together to look at the soil in microscopic detail and see how it is alive. As Hari Byles of Roving Microscope says: “Soil is a living community that cares for us as we care for it” .

Healthy soils provide benefits which stretch in time and space beyond their current geographical location - through carbon capture, flooding prevention, water management, food production, supporting biodiversity, and so on. Soils should be viewed in a similar way to air and water, as something which it is in everyone’s interest to actively take care of. Humans can actively support the microbiome and structure of the soil by growing using agroecological methods, and building soils locally as opposed to importing soils extracted from ecosystems often under threat elsewhere. Work such as that of the Roving Microscope share with the political agroecology movement an ethos of soil care. In order to insert principles of agroecology within the hearts and minds of urban communities, work is needed to deepen people’s understanding of soil, the life it supports, and how to care for it.

Prioritising soil-based growing

Conversations and pilot projects related to food growing in urban areas are frequently becoming disconnected from the soil rather than encouraging reconnection with it. Take La Cité Maraîchère for example, a vertical farming project in Romainville, Paris. A project of five million euros, of which 2.5 million of state funding. In itself a noteworthy project, but one that becomes problematic when it is used as an excuse for the ongoing destruction of remaining historical soils in urban fringes and beyond. There is a disproportionate attention paid to vertical agriculture and roof gardens in contemporary urban agriculture debates. These often depend on soil extraction elsewhere, or remove soil from the process entirely in the case of high tech ‘solutions’ such as hydroponics. Imagine what would be possible if this type of funding would be redirected towards the development of soil-based growing, for example enabling access to land and resources and nurturing new solidarities and new relations between soils, species and people.

Cooking together is a good start

The network of the Cuisines de Quartier started in Brussels in 2019, originating from several previous action-research projects looking into the accessibility of healthy and organic food. Of course, the price came up as an issue in these trajectories, but also the lack of decent kitchen infrastructure and time for cooking, and cultural and dietary differences were identified as obstacles. As such, the non-profit organisation supports mostly self-organised community groups to frequently cook together and connects them to kitchens, for example the one of a local community centre or school. Although inspired by the Cuisines Collectives in Quebec, the network of Cuisines de Quartier (neighbourhood kitchens) specifically does not only target precarious groups, but strives to be a movement with a big diversity of groups that can learn from each other. Several activities are set in place within the network to link to agroecological initiatives, such as pedagogical activities and games on needs, cultural habits and demands, understanding of additives and the food system and visits to agroecological farms. Similar initiatives exist in cities around the globe and flourished during the Covid pandemic. Community kitchens like the Cuisines de Quartier cannot be reduced to mere physical infrastructure but function as an empowering device and work effectively as a piece of social infrastructure with the potential to reconfigure the labours and relations of social reproduction out of charity models.

When agroecology reorganises your municipality

“Agroecology demands the complete reorganisation of municipalities. People from social economy, food production, the environment, health and planning, they all have to work as one multidisciplinary team.” according to Raul Terrile, one of the driving forces behind the Urban Agriculture Programme of Rosario. “ Key member of the agroecological movement joined the ranks of the municipal administration and reached out to their new colleagues across different departments. It set off a wave of collaboration and capacity building across the urban administration that ensures the rootedness of healthy food in the capillaries of urban policies and investments.

Dormant public land was made available; the former plant nursery for urban park management became an agroecological reference centre; parks were turned into garden parks, urban waste streams resourced for composting, buffer strips between roads rendered productive; the housing department started to stimulate growing on terraces and balconies; hospitals provided land for medicinal gardens; prisons set up demonstration gardens and many schools today cultivate their own educational garden. Looking at the list of what has been set up in the last 20 years, one begins to see the cross-over between urban and agroecological infrastructure. This summary can be read as a wish list for a future urban centre for agroecology. It is the result, however, of a persistent and consequent strategy to wield agroecology as an integrating and transversal urban strategy and bundle public investments accordingly.

The Rosario Agroecological Centre (CAR) is a public space that was implemented in 2017 within the framework of the Urban Agriculture Program of the Social Economy Secretariat of the Municipality of Rosario, to seek innovative responses to the demands of new actors interested in urban agriculture. The centre played an important role in valorizing and giving visibility to the knowledge and techniques built jointly in the territory during the last 30 years. The CAR works with research institutes, educational institutions, orchard organizations and non-governmental organizations, social movements and is associated with the Secretary of Extension of the National University of Rosario, the Polytechnic Institute, the Ministries of Production and of Health of the province and the Secretaries of Health, Environment and Production among other municipal dependencies; the Municipal Employees Association (AMTRAM), the Institute of Physics Rosario (CONICET – National University of Rosario), the National Institute of Agricultural Technology INTA and the Association for Biological-Dynamic Agriculture of Argentina.

Agroecologically articulated water policy

As part of the development of its urban food policy, Paris set out a clear ambition for the management of its drinking water catchment areas: develop organic farming areas in water catchment areas and in that way increase the overall supply of local organic food. The public company in charge of the city’s drinking water distribution System, Eau de Paris, is promoting and supporting the preservation and development of organic agriculture. In addition to offering technical support, tools and advice for existing farmers to convert to organic agriculture, the city also developed an active land policy to make land available to organic farmers through an ecological lease (“bail rural environnemental”).

The city is examining legal possibilities for supplying Parisian collective catering with produce from catchment areas, and is also working on a label to promote the origin of products from catchment areas.

Taking root in neighbourhoods

Rosario’s municipal Urban Agriculture Programme is founded on the concept of the ‘huerta’- a garden park where residents can be assigned a plot of land so that they can grow vegetables for consumption and for sale. The huerta provides a focal point for the development of ‘productive neighbourhoods’, in which agriculture is integrated in social economy programmes focused on construction and maintenance. The huertas also provide nutrition, education and employment for residents, who can sell directly or through markets and specialist retail outlets which are also supported by the Urban Agriculture Programme. They are also spaces open to the community who can enjoy the garden parks, purchase the locally produced crops and find out more about food growing in general. These public gardens - located on both public and derelict private land - form part of a decentralized model of municipal management and aim to provide both a growing space and a market within each neighbourhood. The 2 hectares Parque Huerta Oeste, inaugurated in 2020, is the most recent of 7 garden parks in the city.

Proximity matters and comes at a price

Thünen, Johann Heinrich von, Der isolierte Staat in Beziehung auf Landwirtschaft und Nationalökonomie (Rostock, 1842)

In the early nineteenth century, a German economist, Johann Heinrich von Thünen, studied how agricultural production organises around an isolated city. His model "the Isolated State" gives a mathematical explanation for the typical differentiation in land use he observed around German provincial cities based on the economical trade off between the prices within an urban consumer market, cost of land, the cost of transport and the cost of labour. He describes four rings around the city, with the first ring supplying dairy, fruit and vegetables (because perishable), the second ring timber production (because heavy), the third ring bulk crops such as grain (better storable and transportable), the fourth ring livestock farming (self-transporting), and beyond wilderness. Much has changed since Von Thünen's time. Nevertheless horticultural activities remain dominant in a peri-urban environment until today, not so much because there are no alternatives to getting fresh vegetables into the city, but because horticultural activities generate high yields in a small area, and are thus more able than arable farming and livestock farming to cope with high real estate prices and pressure on peri-urban land. From a 21st century perspective the “Isolated State” reveals the logics of substitution at play in a contemporary urban land market, where it has become possible to trade agricultural land use for urban activities that correspond with a higher land value. One of the main causes for this structural substitution is the relatively low cost of transport of (even fresh) food over long distances and the replacement of local land and labour for the extraction of resources and the exploitation of labour elsewhere. While these logics of substitution seem to make room for housing and amenities, and enable urban development, they are at the heart of a way of urbanisation that seems to accept the steady loss of land and farmers which are essential to the organisation of an equitable and sustainable urban society.Can we imagine the strategies and type of projects to revert these logics of substitution?

Practice at the heart of learning approaches

Diálogo de Saberes – roughly translates to ‘Wisdom Dialogues among different knowledges and ways of knowing’) – are a central feature to rural agroecological learning in La Via Campesina. Understanding how Diálogo de Saberes translates to urban spaces through Freire-inspired popular education methods (Freire 1970) could be key to unlocking new forms of solidarity and political mobilisation in an agroecological urbanism .

The development of learning approaches tailored to engage in diverse and layered ways of knowing (emotional, relational, memory, spiritual) is an essential element of urban agroecology’s pedagogies. One-to-one mentoring, training the trainers, holding political dialogues, and practical approaches are often named as more suitable to cater to the different life experiences of people that have rejected homogenising and homogenised approaches to learning. Co-learning, learning by doing and creative approaches, the affinity between conviviality, social gathering and learning, offer a range of opportunities to build meaningful context to make-sense together. There is, however, a perceived need to invest more explicitly and intentionally in political training as part of urban agroecological programmes, particularly in Europe, to build collective political contextualisation and the approaches needed for urban agroecology such as anti-racist practice.

In taking inspiration from MST (Movimiento Sem Terra) schools often based in rural settings, what would urban agroecology schools look and feel like that engage in practice as politics and support burgeoning movements to be based in solidaristic dialogue and transformative learning?

Paulo Freire (1970(1968)) Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Pedagogia do Oprimido), New York: Herder & Herder.

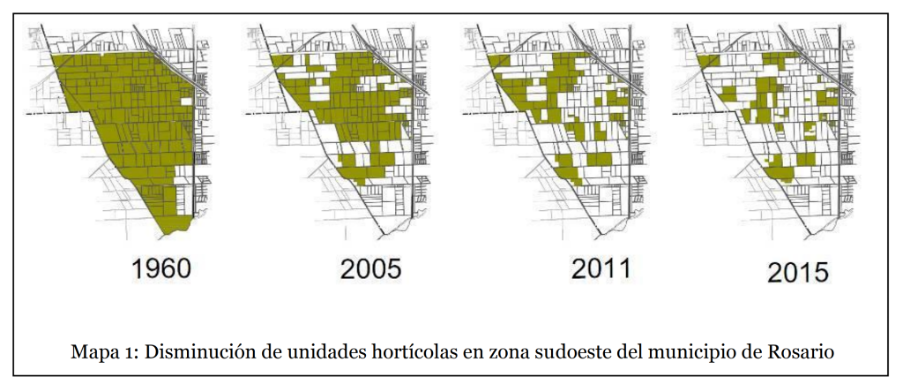

Territorial coordination of municipal public policy

In the city of Rosario, the municipal government agencies are working on a green belt policy (Cinturón Verde) within the development of current agroecological policies. The Cinturón Verde is conceived as the coordination of the efforts to promote and facilitate the transition towards agroecological production by combining multiple aspects of public policy on the largest portion(s) of farmland within the municipal boundary. The greenbelt policy is aimed at achieving favorable living and working conditions to produce agroecological food, protecting farmland from gradual conversion for other uses such as residential and industrial. The Peri-Urban Green Belt Program combines the implementation of different municipal ordinances (i.e. the prohibition of glyphosate throughout the city and of agrochemicals in the first 100 meters of the urban limit, the protection of food-growing lands (800 hectares), the obligation to incorporate food-related industries within the areas of integration with industrial zones), and active collaboration with farmers reconverting back to agroecological farming. This collaboration includes accompaniment for the remediation of upper soils, the introduction of alternative water and energy technologies, the offering of training and expert advice on agroecological cultivation and marketing. The green belt policy shows that a municipal authority can go a long way by using multiple policy instruments in a territorially coordinated manner, linking up with other organizations, institutions and neighboring municipalities.

Community Kitchens as Places of Solidarity

“I will now speak of the immense impetus I believe co-operative housekeeping would give to farming, and the revolution it would bring to it. [...] It will be the first aim of the co-operative housekeepers then, [...] to secure for each society a landed interest of its own.”

C.F. Pierce, Cooperative Housekeeping, 1870

The historical movement for co-operative housekeeping brings the burgeoning reflection of cooperative enterprise of the workers movement into the sphere of domestic work. Pierce's revolution begins in the kitchen and in the de- and reconstruction of the many social, political and economic relations wrapped up in it. Taking control of the kitchen is taking control of the many relations of dependency reproduced in everyday life. Today this translates directly into the decolonial struggle and unexpected forms of solidarity that come out of community kitchens.

A transformative community kitchen based on the principles of agroecology can play a pivotal role in the radical restructuring of the entire food system, including both relations with producers (near and afar) and urban consumers. By accessing urban and peri-urban land or liaising with peri-urban farmers they can contribute to develop a territorial food system, mindful of farmers’ livelihoods. By making the food broadly accessible, it addresses injustice in the availability of healthy food for all. By cooking and eating together, it can break with patriarchal and individualised approaches to food. By also sourcing food overseas from agroecological farmers, it can make available culturally appropriate food to a wider group of people. By organising forms of political engagement and knowledge sharing within the territory, alongside convivial initiatives, the kitchen can encourage the broader resourcefulness and solidarity, vis-a-vis the neoliberal city.

Growing community spaces

In 2017 a consortium of community organisations took on management of the 2.5 acre Wolves Lane Centre, a council owned ex plant nursery site containing a number of large glasshouses in Haringey, North London. The vision for the site is to develop a thriving community food project with opportunities for collaboration with and involvement of Haringey residents in education, enterprise and health and wellbeing activities. This is also reflected in the consortium of actors behind the management – or better, stewardship – and process of renovation for the site, ranging from community-based actors (Ubele Initiative), organic growing and training (OrganicLea) and local food distribution organisations (Crop Drop) to land advocates (Shared Assets) The consultative design process lead to a development plan for the Wolve’s Lane Centre (see also here) that includes public events/community building connecting people with the outdoor and indoor growing spaces, allowing reallocation of glasshouses currently used for this purpose and fit-for-purpose new facilities for community learning, community hires and operational activities.

Wolve’s Lane is inspiring in light of the search for an agroecological urbanism, as it reveals how residual urban infrastructure – in this case, a former municipal plant nursery – is re-interpreted as a community-driven space where agroecological principles permeate a series of local initiatives and construct a set of solidarities between groups pursuing different social and ecological agendas.

Material Feminists against patriarchy

The current dominant approach to food is based on individual choices: people choose what to buy and most worryingly, how much food to waste individually, or as part of their family arrangements. The current food system approach does little to include considerations of what food is available, how this relates to a colonial past, and how this is prepared and eaten. Often women are expected to be in charge of food preparation even when they have caring responsibilities and a full time job outside the home. However, the emerging community kitchen movement can build on the historical imaginary of the materialist feminist movement of the late Nineteenth century, which has been envisioning a world in which kitchens where part of social collective arrangements, rather than individualised segregated spaces aligned with patriarchal oppressive family structures.

“The Grand Domestic Revolution” - book cover

A multiplicity of spatial and social arrangements were experimented and designed: from kitchenless houses with shared housekeeping facilities, to large scale co-housing /neighbourhoods with central kitchens (see image). Contemporary, agroecology-based and politically-active community kitchens can help to reconsider food and meal production as a collective responsibility, challenging patriarchy and colonialism both in the fields and in the house.

© Hayden, as cited in DICK URBAN VESTBRO and LIISA HORELLI (2012), “Design for Gender Equality: The History of Co-Housing Ideas and Realities” in Built Environment, Vol. 38, No. 3, Co-Housing in the Making (2012), pp. 315-335

Fighting the struggle of housing and growing rights together

The Land Justice Network is a coalition of grassroots actors in the UK that have started up a series of remarkable initiatives around a people-driven land reform, placing principles of the equitable sharing of land at the core. One of the notable things about the coalition of partners behind the Land Justice Network is that it not only includes groups mobilising around access to land for growers and land workers but also groups that are fighting for housing rights, and more generally groups focussing on decolonisation. The People's Land Policy is a shared mission statement referring to the People's Food Policy by the Land Workers Alliance. The strength of the coalition is the clear desire to fight the various struggles over land together. Where current capital-driven processes of urbanisation play various forms of land use against each other, using bidding rent and market competition as the determining factor in allocating land, the People’s Land Policy inspires us to imagine an agroecological urbanism where the use value of soils becomes a leading factor, and where the reproduction both of the right to live and to cultivate are secured together rather than in competition.

Growing space as planning requirements

Cueillette des Pommes à la cité‐jardin – Le Logis-Floréal À Watermael-Boitsfort, 1940

The Ferme du Chant des Cailles is a collective urban agricultural project initiated by farmers together with local citizens in a residential neighbourhood in Watermael-Boisfort, in the south-east of Brussels. The land on which the farm was established lies in the heart of the Logis Floréal, a garden suburb developed in the 1920’s designed by Louis Vanderswaelmen. The land was reserved in the original plan for a farm that was never built, but the settlement included individual productive gardens, productive fruit trees in the public domain and an orchard. The pressing need for new social housing in Brussels led the authorities to consider the land historically reserved as a productive space for the construction of 250 additional housing units, especially since the social housing company was owner of the land. However, the mobilisation of local citizens put the process of the development project on hold. The coalition of citizens even mapped vacancies in the neighbourhood, questioning the need for new development. What started with the idea of repurposing an abandoned field developed into a process of reappropriation of a historical urban pattern, relinking housing and food production, underlining the need for new planning tools and processes that consider community-build food production as equally valuable on the urban agenda as housing, schools or playgrounds.

Historical plan of Louis Vanderswaelmen with the historical productive land that today hosts the Fermes du Chants des Cailles highlighted

Matryoshka doll farmers

“Andre is the arable farmer and we shift with him in his crop rotation. We move with our 3 hectares every year within his 100 ha farm.”

Farmers of Tuinderij De Stroom for Future Farm Films

One of the most common problems that starting agroecological farmers face today is the lack of affordable access to land. However, this struggle occasionally leads to unexpected alliances with larger-scale agricultural practices. In the province of Gelderland in The Netherlands, the market gardeners of Tuinderij De Stroom found access to 3 ha of land within the crop rotation of an existing 100 ha organic arable farm Ekoboerderij De Lingehof. Just as a Russian Matryoskha doll fits within a larger doll, the one farm – De Stroom – operates inside the larger one – De Lingehof. The cooperation not only creates much-needed access to land for new practices, but also brings many additional benefits, such as the sharing of infrastructure (washing facilities, place to eat...) and interconnected services (purchase of agricultural products for vegetable packages, ploughing for the horticultural activities, availability of labour at peak times...)., but also closing cycles and establishing equilibriums (e.g. manure and composting, shared rotation schemes, etc.) and sharing knowledge and techniques between different generations of farmers. Moreover, this farm-within-a-farm model could be more systematically pursued as a valuable transition strategy in light of the lack of succession within farming families. Retiring farmers can build up the trust with the new entrant farmers to hand over their life’s work in good conscience, while the new entrant farmers get the time and literally, the space to acquire the experience to manage stepwise larger amounts of land.

A translocal network of agroecologists

The Red de municipios por la agroecología is uniting several Spanish municipalities and local organisations since 2017 with the mission to link social services with food policies. The approach is translocal as it tries to build mutual support between local authorities. The network engages in a wide range of support and facilitations activities. Two members of each city are compensated to attend the monthly meetings where they share experiences, guaranteeing the active participation of the municipalities. There is a technical advisory team supporting the network, composed of all (former) farmers or pastoralists that have followed an agroecological training. They help out the public servants, for whom agriculture is traditionally not part of their standard policy tasks and mediate between different authorities on what could be feasible or desirable from a technical agroecological perspective. As such, they are able to link policy with concrete action; they coordinate wholesale markets geared towards more local produce, they set up farmstarts, small processing centres, composting infrastructure, mobile slaughterhouses and a local labelling system. Parallelly, they continue to develop the capacity building of network attendees by organising monthly webinars and offering customised programmes depending on the size, history and capacity of the city. While the interest in agroecology in the bigger cities (and their environmental departments) usually stem from both the organisation of their environmental goals as well as the upgrade of new and existing community gardens, the old Arab cities in Spain have an active agricultural department and are looking for technical insights, since they still have productive lands within their municipal boundary. In smaller towns, the technical team collaborates more with economic departments and positions agroecology as an experiment for alternative rural development. By not focussing directly on physical infrastructure but rather on training and capacity building within administrations and mediating between different policy sectors, the network is able to lobby local policy from a very concrete, action-based perspective that transcends political tenures.

Organic waste from a farmer's perspective

“I don't want urban organic waste on my farm. Keep your waste please. Wood chips on the other hand you can drop off as much as you want.”

Tijs Boelens, farmer of De Groentelaar

Usually discussions about repurposing the large volumes of organic ‘waste’ produced in cities for soil building and food growing start from an urban perspective where the views of farmers are sometimes seen as of less importance. However, farmers are rather apprehensive about the use of urban organic waste and are interested in specific nutrient sources, especially those that are hard to resource on farm. There are examples of farmers working with the parks & green departments to recuperate for example leaves, but a lot of barriers need to be tackled such as transport or legislation.

Thinking about resourcing nutrients in (peri)urban environments could start much more from the specific needs of agroecological actors and then look at how to find, produce, collect, store and make them available in an appropriate way. This has been the strategy followed by the urban agroecology centre in Rosario, where research is being carried out on urban waste streams to ensure farmers are clear on what they contain and whether they are suitable for incorporation into agroecological production.

The agroecological park as sheltered space and enabling environment

The agroecological park is a sanctuary space, shielded from the dominant context, in which other rules can be set and favorable conditions for agroecological farming created. This may come in the form of training, of specific ‘test spaces’ (as in the Pede Valley in Brussels). This may also come in the form of specific infrastructure (land readjustment, composting facilities, processing facilities, machine sharing); the building of shared management and maintenance capabilities; training and technical assistance; cancellation of unnecessary roads, land readjustment, the reintroduction of hedgerows, and other small landscape elements; water harvesting infrastructure (on and on off farm); etc. Park management may also come with shared marketing strategies, food processing and conservation, shared logistics, labeling etc. (Parc Agrari del Baix Lobregat).

Building territorial governance capacities

The paradigm of the eco-regione or bio-region comes with the desire to reconnect the urban agglomeration to the ‘natural’ regional geography that precedes urbanisation (foodsystemchange.org). Dynamics of urbanisation overwrite a pre-urban geography, threatening the hydrological integrity of the region, the soil structure, the nutrient cycles, the biodiversity, etc. Particularly inspiring is the way in which many eco-regional initiatives start from self-imposed ecological and territorial boundaries and re-think urbanisation as part of the care for the landed resources within the particular region.

In the German and Austrian context we can witness many Öko-region initiatives. Most of them have their origin in the promotion of organic farming (not in agroecology per se). The focus on organic farming cements the link between regional policies and soil care (ie. Ökoregion Kaindorf and the Humus+ project). Soil and farming are recognized as the necessary basis for an ecological regional geography. These initiatives do establish a strong connection between resource sovereignty and an understanding of territorial control built around place-based solidarities between actors within a region, and move well-beyond protectionist and identitarian regionalist logics. They give farmers a potential place within regional constituencies, and indirectly a place in the territorial governance of urbanisation, a place often denied to them within urban and metropolitan territorial governing bodies.